The mind-blowing question | Online book launch Sat Jan 25th: Join live & win prizes!

Happy New Year Making Change Stickers!

Welcome to the new subscribers who have joined since my inaugural post on the origin story of the Making Change Stick programme.

In case you haven’t seen it, you may also be interested in a recent post from my other Substack, Rethinking Education, on how writing the Making Change Stick programme has improved my personal life in various ways.

I’d like to share two things with you in this post.

1. Invitation to the online book launch

We’re hosting an online book launch on Saturday 25th January, from 11am-12 noon UK time. Don’t worry if you’re not available at that time, we’ll send out a recording afterwards. The rough plan is as follows:

11-11.30 - I will be interviewed by the wonderful Rachel Macfarlane

11.30-11.45 - Audience Q&A

11.45-12.00 - Competition and prize-giving. Prizes include:

A 3-year subscription to the Making Change Stick online training suite for your school or organisation (worth up to £3950 - Ooooh!)

A 1-hour implementation coaching Zoom session

5 signed copies of the book

To be in with a chance of winning, you need to join us live.

You can register for free here.

2. The mind-blowing question

What proportion of school improvement initiatives actually improve pupil outcomes?

Over the last five years or so, I’ve asked this question to thousands of teachers, leaders and support staff all over the world. I never tire of doing so, because the responses never fail to blow my mind.

You may wish to look away from your screen for a moment while you consider this question. If you can, try to come up with a percentage figure.

When I ask this question, I often initially notice some interesting nonverbal responses. People laugh; they smile; they roll their eyes; they raise their eyebrows; they cast uncertain glances at one another; and they pull unusual facial expressions as they scroll through their memories and try to arrive at a ballpark figure.

Perhaps you’re lucky enough to have worked in incredibly well-run schools, and your answer to this question is quite high. If so, congratulations – you won the lottery. Because in my experience, the vast majority of people respond to this question with a figure in the region of 10–20% – an estimate that is backed up by the available evidence, as we’ll soon see.

Clearly, a failure rate of 80–90% is somewhat suboptimal. But the story does not end here.

Whatever figure you came up with, we’re now going to tighten the criteria a little. As you look back over your career to date, what proportion of school improvement initiatives would you say meet the following conditions:

The initiative led to demonstrable gains in pupil outcomes.

There is evidence of causation (i.e. you have data that connects the improvement initiative to the improved outcomes).

The gains were sustained over several years, and are still happening now.

Again, you may wish to take a moment to reflect on whether you need to revise your figure in light of these criteria.

In my experience, at this point many people revise their figure down to somewhere around 0–5%. Or they may point to an initiative they believe to be impactful, but then say, ‘We don’t really have compelling evidence… we just think it’s effective.’ Or perhaps, ‘There are definitely pockets of effective practice, but I wouldn’t say it’s working everywhere just yet.’

At this point you may be thinking, ‘Hang on a minute. This all sounds a bit anecdotal. Where’s the evidence?’ If so, great! You’re already thinking like an implementation scientist.

In truth, it’s not possible to arrive at an accurate answer to the question. People tend not to publish detailed accounts of things that don’t work. Also, it largely depends on how you define and measure ‘improved pupil outcomes.’

But we can look for clues – and they all point in the same direction. Let’s look at three: experts in change management, the available research evidence and teacher surveys.

Clue 1: Experts in change management

John Kotter is Emeritus professor of leadership at Harvard Business School and a world-renowned expert on organisational change. If you’ve ever done a school leadership course, you may be familiar with his eight-step framework for leading change. In his book, A Sense of Urgency, Kotter wrote:

From years of study, I estimate today more than 70% of needed change either fails to be launched, even though some people clearly see the need; fails to be completed, even though some people exhaust themselves trying; or finishes over budget, late and with initial aspirations unmet.

Kotter does make clear here that this is an estimate based on his experience working with many organisations over several decades, including, but not limited to, schools. But this figure of 70% comes up a lot. For example, in an influential paper published in the Harvard Business Review, Beer and Nohria wrote, ‘The brutal fact is that about 70% of all change initiatives fail.’

To be clear, some people have contested this figure of 70% and think the real figure is much lower, while others think it may even be higher. And Kotter, Beer and Nohria were talking about change initiatives generally (i.e. in businesses and other large organisations) rather than in education per se. But the 70% figure provides us with a kind of background reading as to the estimated failure rate of change initiatives in any large organisation.

In education, the situation is no better. In their book Learning to Improve: How America’s Schools Can Get Better at Getting Better, Professor Anthony Bryk and his colleagues at the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching – leading exponents of improvement science in education – powerfully summarise the research evidence:

By definition, improvement requires change. Unfortunately, in education change too often fails to bring improvement – even when smart people are working on the right problems and drawing on cutting-edge ideas. Believing in the power of some new reform proposal and propelled by a sense of urgency, educational leaders often plunge headlong into large-scale implementation. Invariably, outcomes fall far short of expectations. Enthusiasm wanes, and the field moves on to the next idea without ever really understanding why the last one failed. Such is the pattern of change in public education: implement fast, learn slow, and burn goodwill as you go.

Perhaps one reason so many change initiatives fail to improve anything is that people tend to focus on the former – change – rather than the latter – improvement. As Viviane Robinson explains in her illuminating book, Reduce Change to Increase Improvement:

To lead change is to exercise influence in ways that move a team, organisation or system from one state to another. The second state could be better, worse or the same as the first. To lead improvement is to exercise influence in ways that leave the team, organisation or system in a better state than before. […] Good ideas sometimes fail to generate reliable improvement because neither the advocates nor the implementing agents know how to execute them in ways that achieve the intended improvement.

This phenomenon, whereby schools implement an endless stream of ‘good ideas’ that fail to achieve the ‘intended improvement’, leads to a condition that goes by many names, such as:

Initiative-itis.

Innovation fatigue (or fad-tigue).

‘This too shall pass’ syndrome (a phrase often muttered under teachers’ breaths as the latest wheeze is announced).

Whenever I mention the phrase ‘this too shall pass’ before an audience, a ripple of laughter spreads through the room – the laughter of recognition. Initiative-itis is all too familiar to anyone who has spent more than a year or two working in schools.

But while it may raise a wry smile, it’s important to recognise that this condition is horribly corrosive. It makes people sceptical and increasingly cynical about the idea that lasting, positive change is even possible.

Clue 2: The available research evidence

As we’ve seen, it isn’t really possible to quantify the extent to which school improvement initiatives are effective or ineffective. But we can catch glimpses here and there in the research literature – and it’s not a pretty picture.

In 2010, the UK government established the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), which describes its mission as ‘breaking the link between family income and educational achievement […] by supporting schools to improve teaching and learning through better use of evidence.’

Part of the EEF’s remit is to carry out lots of medical-style randomised controlled trials, evaluating the impact of ‘high-potential projects’ to generate new evidence of ‘what works.’ At the time of writing, the EEF has completed 211 projects, with a further 68 currently underway. Of the 211 completed projects, only 65 had a positive impact on pupil learning outcomes. This gives us a familiar failure rate of 69.2%, which seems particularly high when you consider that initiatives evaluated by the EEF are screened and selected on the basis that they demonstrate ‘high potential’.

Elsewhere, the picture looks even less rosy. In one recent longitudinal study, researchers evaluated the impact of 411 leaders of UK schools and found that only 62 of them were able to bring about sustainable improvements at their school – a failure rate of around 85%.

Turning to the international research literature, again a familiar picture emerges. To share just one eye-watering example, in recent years the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation invested more than $2 billion in an attempt to improve educational outcomes by breaking up US schools into smaller ‘schools within schools’. As Bill Gates later reflected, ‘Simply breaking up existing schools into smaller units often did not generate the gains we were hoping for’, a finding that he described, with admirable understatement, as ‘disappointing’.

Clue 3: Teacher surveys

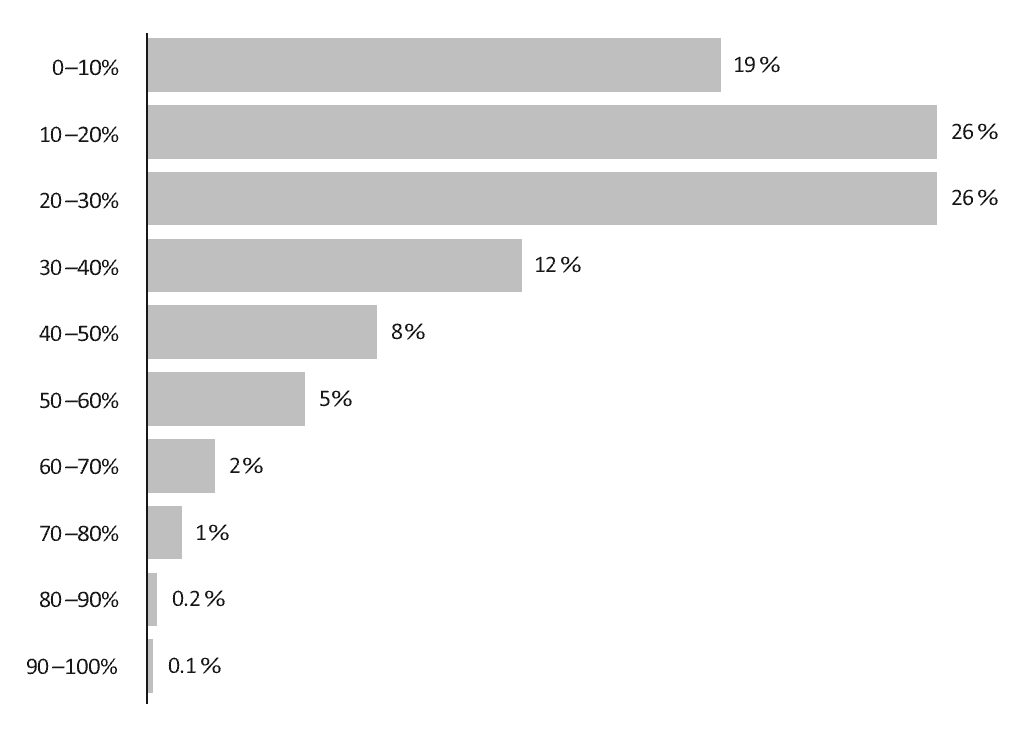

In January 2024, the teacher polling organisation Teacher Tapp kindly agreed to run my ‘mind-blowing question’ past the 10,000 or so teachers on their database. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of the responses.

As you look back over your career, roughly what proportion of change initiatives demonstrably led to improved pupil outcomes, which were sustained over several years?

Figure 1 – Teacher responses to the ‘mind-blowing question’

To summarise the findings of this survey:

19% estimated the success rate to be lower than 10%.

45% estimated the success rate to be lower than 20%.

71% estimated the success rate to be lower than 30%.

Implementing school improvement is no picnic

To recap the story so far: according to leading experts in change management, to the available research evidence and to teacher surveys, the proportion of school improvement initiatives that bring about lasting, positive change is consistently low – somewhere around the 20–30% mark at best, and probably a lot lower.

This is somewhat suboptimal to say the least. In schools, there are often at least two or three significant change initiatives happening at any given point in time. It sometimes feels like the only constant is constant change. So, the fact that the vast majority of school improvement initiatives don’t actually improve pupil outcomes is not an inconsequential problem. This. Is. Huge.

This is not to suggest that teachers, leaders and support staff don’t make a difference. On the contrary, educators make a difference every single day just by turning up and doing what they do. We’re talking here about school improvement – the art and science of improving educational outcomes at the level of schools (or groups of schools, or the system as a whole) so that current and future generations achieve better outcomes than those who came before.

Nor should we be too hard on ourselves. If you’ve ever made a new year’s resolution you probably know that ‘making change stick’ is easier said than done. Whenever I’ve tried to improve an aspect of my own life – to read more novels, to exercise daily or to eat more healthily, say – I’ve often found it’s fairly easy to keep it going for a week or two. But if you fast forward a few more weeks, it’s likely that the good ship ‘self-improvement’ will have run aground.

I’m far from unique in this regard. A recent analysis of over 800 million activities by the exercise app Strava found that, on average, people give up on their new year’s resolution on January 19th. They call it ‘Quitters Day’.

Of course, bringing about lasting, positive change in our lives is possible. I struggled for years to establish and maintain healthy habits around things like exercise, diet, sleep, reading, meditation and technology addiction. My wife used to complain that I was forever buying books with titles like ‘365 Ways to Be More Productive Without Actually Doing Anything’. I’ve now made huge progress on each of these fronts, thanks in part to many of the ideas in this book. But it has been no cakewalk. Literally!

If it’s hard enough to pick up a novel, take yourself to the gym or resist the doughnuts in a staff meeting, then bringing about lasting, positive change in a large, complex organisation like a school starts to look fiendishly difficult.

So, I want to be really clear. Making change stick in schools – motivating and mobilising a large, diverse group of people to all start consistently pulling in the same new direction in such a way as to bring about sustained, improved outcomes for current and future cohorts – well, let’s just say it’s no picnic.

Bringing about lasting, positive change in schools is possible. There are many examples of schools that have improved almost beyond measure. It’s just that there are many more examples of school improvement initiatives that fail to meet their stated aims.

The question is, why?

In my next post, we’ll look at two of the main reasons:

Teachers and school leaders aren’t taught how to implement change effectively.

There are many problems associated with top-down change – and top-down change is our default model.

Until the next time…!

Oh and don’t forget to sign up to the book launch!